INTERVIEW WITH ISABELLA LI KOSTRZEWA

Isabella Li Kostrzewa in the photo

(Details on the artist’s outfit)

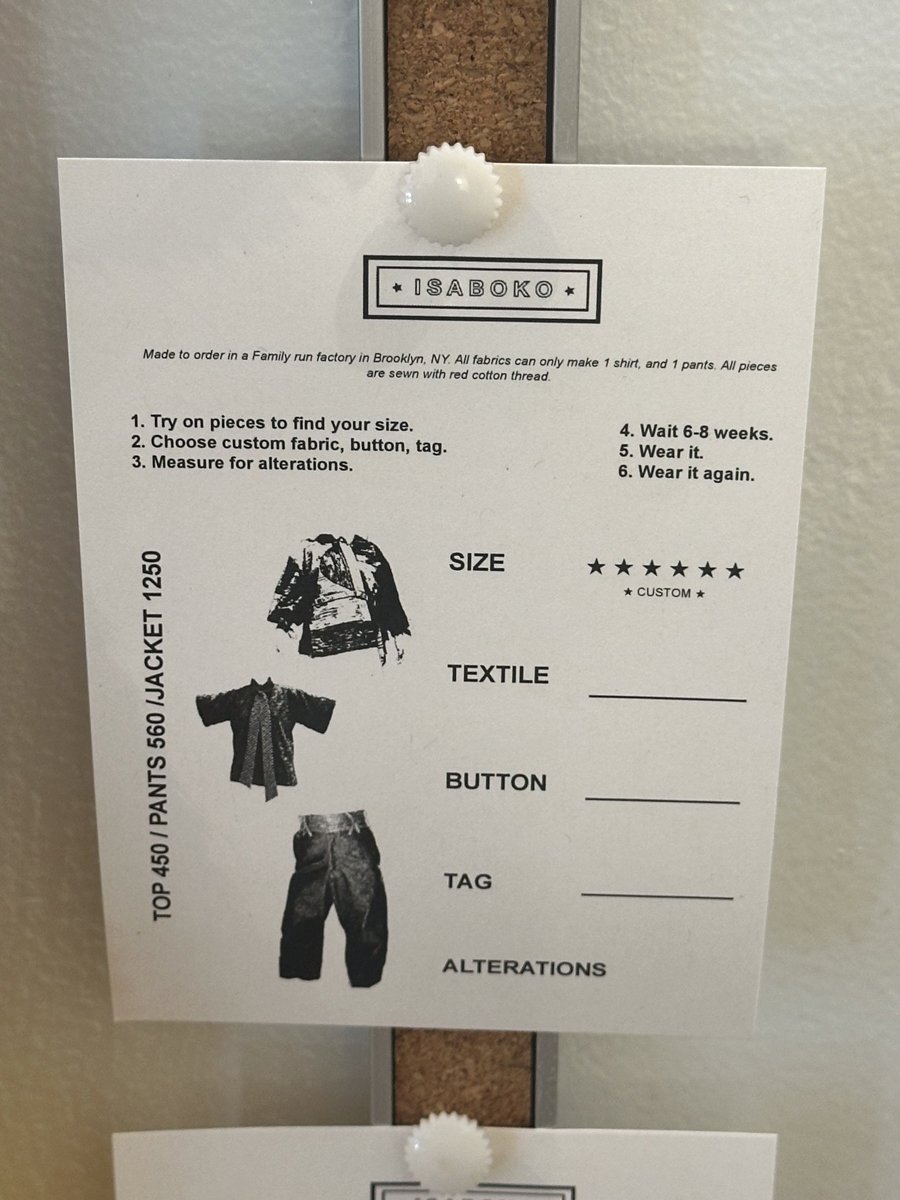

Isabella Li Kostrzewa talks about sustainability like they were born to do it. A fashion designer based in Brooklyn, Isabella, founder of Isaboko, “Isaboko is a mix of my name but it is also meant to sound gender-free, and it could be from anywhere in the world. It’s just a word that I made up,” which creates garments out of materials that have uncommon pasts. Isabella, known to their friends as Izzy, was born in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan. Their first collection consists of gender-free skirts, transformable tunics, patchwork hoodies, silver and brass bolos and made-to-order jackets, shirts, and pants. Isaboko will provide you with whatever you want to clad yourself in, you just have to be more thoughtful and choose sustainable. Isaboko has a positive outlook on the future and thinks that humans and civilization can survive peacefully with the environment. The garments that Isaboko produces will exist in the future and provide hope for now. The collection ranges from $75 to up to $1,250 for made-to-order jackets, but the patterns for most of the pieces are available for $15 to anyone who knows how to sew.

While Kostrzewa was sharing their thought-through thoughts with PhotoBook Magazine in their parasol projects sponsored pop-up at 251 Elizabeth St, a SoHo resident apologized for interrupting the interview and said “Your designs are very cool!” Not only are their designs cool, but their train of thought and how they look at the world, constantly making relentless efforts to save the planet fashionably is super cool too.

Suppose you had to describe Isaboko in three words. What would they be and why?

Whimsicality, utilitarian, and solarpunk. Whimsicality because I love to play with a lot of fun bright colors and kind of silliness and joyfulness. Utilitarian because I still want the clothes to be worn and to be seen like you can run and ride a bike in these clothes. Solarpunk is a new, literary, political, and creative movement that is growing quickly, although it’s still very small. It’s an idea that humans can and are actively working towards saving the world. We are building systems to help the climate, and we shouldn’t feel hopeless. Rather we should be optimistic and work to save the planet. We shouldn’t think about, “Oh we need to live on Mars and it’s over, we need to build bunkers and live in them.” The conversation should lean toward the trajectory of preserving the earth since we can do it and we are doing it. And I think my brand plays into that, both in a visual way—like how the clothes look and in the production—like we only use waste textiles, zero-waste patterns, gender-free designs, we care about diverse perspectives. That for me is the solarpunk world.

Isaboko uses a unique yet fascinating sizing chart that allows you to adjust up to six inches to style clothes differently and embrace the body's natural changes. Further explain how you make these clothes capable of this and why?

I care about fat liberation. It’s this idea that fat-ness is not bad and whatever our bodies look like is good. There should be clothes that fit your body well. So many brands just have sizes limited to small, medium, and large. Although I’m a brand-new line, it was important to create clothes that fit a lot of people. Also, one of my mentors is Lelia Kelleher who is making the first comprehensive plus-size patterning book. I was her research assistant. I learned a lot about the concept from her. For instance, how to make clothes for different body sizes that would look good on them and would embrace their bodies. Plus, everybody’s body is changing all the time, like if you wear a pair of jeans in summer which don’t fit you anymore, that’s an unpleasant feeling.

What points do you keep in mind when you design gender-free clothing? What elements do you include that would make all genders feel inclusive of Isaboko's clothing?

At the end of the day, anyone can wear whatever they want. A man can wear a tight-fitted corset and dress, which could be labeled as feminine. Everything inherently is gender-free. The intention is to think about, would an average man or woman like to wear this and think it’s accessible to them. For example, in my tanji tunic design, at first instance, you would think it’s a dress but you can also wear this as a buttoned-down shirt and wear it over pants.

Is there a specific fabric that you usually prefer working with and why?

I love working with any waste material, especially the ones that have a unique story. The jackets are made from summer camp cabin covers that were in use. I love using Japanese textiles. I have these upcycled hoodies in my collection, created from old-American unfinished quilts and embroidery, and 80s and 90s girl scout patches. So, it’s mostly fabrics with a distinct past.

What is your biggest ick apart from the existence of fast fashion brands?

(Laughs) Fast fashion sucks. We need to work together since we have power in our voices. We are in America; we have so much power and wealth. We often tend to forget how much of an impact we have on the rest of the world. My biggest ick is to feel powerless and have no voice for sustainability, despite everything we have. It’s like we’re in the capital in the Hunger Games and we don’t even know it.

There are pieces in your wardrobe that you wear every other day. Please discuss.

I wear this Paiute Made x Isaboko Hat. These hats are from a company’s obsolete deadstock and were headed to landfill. They were rescued and then hand-beaded by Taylor Uchytil the indigenous beadwork artist behind Paiute Made. There is a “solarpunk” patch on the back that was hand embroidered by Joy Nuanez on a 1920s hand crank embroidery machine.

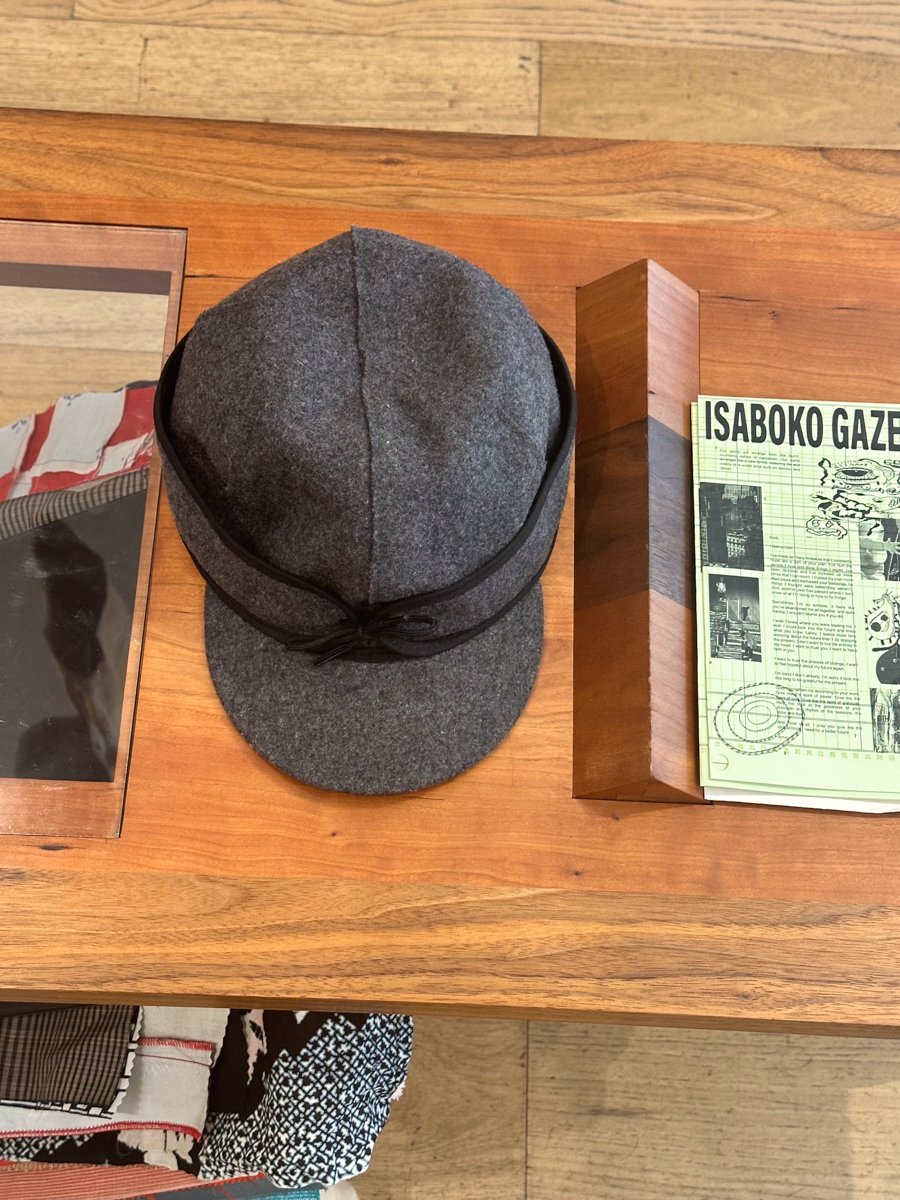

I love being in turtlenecks, my brown cargo pants, and Adidas Sambas or Nike running shoes, I’m ready to run all the time. I also wear the Stormy Kromer cap. It’s this hat brand that the original loggers that were in the Midwest wore. The design started in 1903 and is still made today in a small town in Michigan. It’s a really special hat since I’m from Michigan.

(The stormy Kromer hat)

What initially stimulated you toward sustainability, and what keeps you going?

I grew up wanting to be a fashion designer. I felt deeply for it. My mom encouraged me to take private sewing lessons. So, growing up in Michigan I was taking lessons at this place called Dream Key Design Academy in Mt. Pleasant. I loved it so much but it was hard. The first fifty sewing projects are so horrible and you want them to be so much better but I was getting better day-by-day. At 16, I was on this show named Project Runway: Junior and I made it to the finals. Although it was a great sewing opportunity, I felt negative about how the fashion industry makes you feel bad about yourself and everyone is trying to be better than the other. We completed projects on such intense timelines. There was nothing sustainable emotionally or materialistically about it. But I knew I wanted to be in fashion so I thought of rebuilding my relationship with it. When I got accepted at Parsons School of Design, I was keen to build a new worldview so I could feel good about it. Through experiences, resources, amazing design teachers, and sustainability classes, I learned tons from Parsons. I feel so happy that I got to where I am today. So, in a way, Project Runway: Junior directed me toward sustainability and made me realize a lot of things about the industry. I’m so proud I did it. Clients still come to me and recognize me from the show.

Article by Palak Godara, Contributor, PhotoBook Magazine

Tearsheets by Nicolas Harris, Graphic Design Intern, PhotoBook Magazine